The One to Watch

By Robert Gounley

"Why isn't that man smiling?" asked the little girl sitting behind me.Few heard her question - the cheers and applause drowned her voice. 2000 people in Pasadena's Convention Center were watching a giant TV. The screen showed a room full of people at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, most of them cheering as well.

|

| The aeroshell protects the rover from fiery temperatures as it enters the Martian atmosphere in January, 2004. Artwork NASA/JPL. |

This was the main event of the Planetary Society's "Wild About Mars" convention. Earlier, Society President Dr. Lou Friedman, Ray Bradbury, and TV's "Bill Nye - the Science Guy" had shared their perspectives on Mars exploration. Now, many of us believed the Mars rover Spirit had just safely landed.

Or had it?

I recognized the two engineers in the center of the TV screen. Wayne Lee, providing running commentary, wore a red-white-and-blue polo shirt suitable for the U.S. Olympic Volleyball Team. He looked excited but restrained as he studied his computer monitor for signals from Spirit. Beside him was Rob Manning - his bearded face nearly expressionless. He looked at the monitor like a surgeon studying a patient's vital signs. A minute earlier, he had reported Spirit was bouncing on Mars. That news made a lot of people very happy.

Wayne and Rob weren't smiling. Spirit's signal had disappeared moments after the announcement.

Ask a pilot if flying is hard and he'll tell you that flying is easy. Landings - they're hard!

Ask a space engineer about landing on Mars and he'll tell you it's possible, but only just. A spacecraft approaching Mars travels at about 12,000 mph. The only meaningful distinction between it and a passing meteor is the ability to perform a controlled deceleration to a survivable velocity when hitting the surface. Quite a few Mars missions failed this test - including two that preceded Spirit.

By now, most people have a rough idea of the sequence of events engineers call Entry, Descent, and Landing (EDL). Upon contact with the Martian atmosphere, a heat shield creates a drag brake for Spirit. When no longer useful, the shield drops away and a parachute deploys with Spirit dangling from a long cord below. In the thin atmosphere, the parachute and rover still fall at a fast clip - about the speed of a crashing plane.

Near the surface, giant airbags form a protective cocoon around the rover. Close to impact, rockets slow the assembly to a near stop, followed by release of the rover. It will bounce many times before it can stop and unfold itself on the surface.

The sequence is an unforgiving taskmaster. Each element must work flawlessly and be timed precisely. Failure could result from just a few seconds error in predicting when the parachute should deploy, the airbags should inflate, or any of a dozen other events. All must be programmed in advance for Spirit to respond correctly. In the time required for Spirit to complete EDL, radio signals can only travel a fraction of the distance between Mars and Earth. Ground controllers must sit and wait for evidence that years of planning, building, and testing were done properly. Some call this period, "six minutes from Hell".

The lander missions immediately preceding Spirit were all designed with no communication during EDL. Either they would call back from the surface or they wouldn't. Due to the 1999 failure of NASA's Mars Polar Lander, this would not be an acceptable option for Spirit. If anything goes wrong, ground controllers must know what it so that the second rover, Opportunity, could have a fighting chance.

Before Spirit enters the atmosphere it gets power from its solar powered cruise stage. During EDL, it runs off of batteries and power is scarce. It can produce a radio signal detectable from Earth, but little information can be carried with it. These messages are carried by subtle, but distinct changes in radio tones called "semaphores". The messages will tell ground controllers when every major step of EDL has been completed.

Two NASA spacecraft orbiting Mars-Mars Global Surveyor and Mars Odyssey- provide a second communication path. They each carry a UHF radio receiver to capture messages from Spirit. Orbital mechanics limit contact time to minutes, but in that time huge amounts of data can be dumped into a passing orbiter for replay back to Earth.

|

| Artist's conception of MER rover. Artwork NASA/JPL. |

Even on paper, making these communication paths happen during EDL seemed chancy. Planetary alignments dictated when Spirit had to arrive at Mars; it would be farther from Earth than previous landing missions. Spirit's direct-to-Earth signal would be difficult for NASA's Deep Space Network to detect. While confidence was high that signals could be heard during the start of entry, no one promised that Spirit's semaphores would be heard all the way down. Further complicating matters, the shallow angle required for atmospheric entry required the landing to take place late in the Martian afternoon. Viewed from Earth, the signals would fall out of view soon after Spirit had landed.

These difficulties placed greater attention on the orbiting Mars spacecraft. Mars Global Surveyor would be in view of Spirit during EDL and should obtain definitive data on how events progressed. Each spacecraft's telecommunications system had been carefully designed to assure mutual communications. Unfortunately, they had been built years apart and never had the opportunity for a full end-to-end test. Their first spacecraft-to-spacecraft communication would happen while Spirit landed.

Knowing this, the expressions I saw on the television screen made perfect sense. A room full of space engineers sat ready to receive data from Spirit, but only a few had anything to see. Most of were looking at Wayne and Rob, who could best interpret what the semaphores meant. A dozen or more managers and VIPs stood by. They were looking at Wayne and Rob as well.

Incredibly, the Deep Space Network maintained lock on Spirit's semaphores all the way to the surface. Wayne announced every major event - heat shield deployment, parachute deployment, radar detection of the surface, and finally contact with the Martian surface. It seemed too good to be true.

Then, the signal halted.

This should have been no surprise. Inflating the airbags obstructs Spirit's antenna and degrades transmissions. That the signal could still be heard while the Spirit was bouncing was an incredible feat. The silence probably meant Spirit's bounce had turned the antenna away from Earth. Probably. Mars Global Surveyor could tell us by receiving a signal from Spirit - or not.

Wayne and Rob stared at their screen. Everyone stared at Wayne and Rob. The VIPs looked a little self-conscious, like a hometown crowd who just cheered the end of a close basketball game then noticed there was still time on the clock.

The waiting seemed interminable.

Initial news was tentative. Someone reported that an antenna at Stanford University had detected Spirit's UHF signal all the way from Mars. That would be an astonishing accomplishment - or an embarrassing mistake. Wayne and Rob's expressions did not change.

Another voice reported that Mars Global Surveyor had received a UHF signal. It would be a few more minutes we'd know whether the message was "all's well" or "farewell".

|

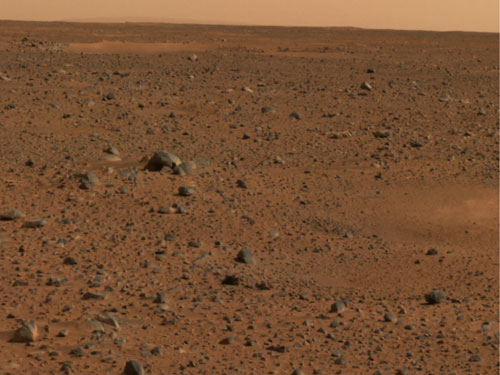

| This is a portion of the first color image captured by the panoramic camera on the Mars Exploration Rover Spirit. Image credit: NASA/JPL/Cornell. (Click to enlarge) |

It was "all's well".

I knew that when Wayne and Rob burst into cheers. Everyone in the JPL control room, the Pasadena auditorium, and presumably all over the world cheered with them.

A few hours later, pictures were on display showing Spirit safely on the surface of Mars. All around it was a wide plain, ready for exploring.

Today, Spirit's future looks bright. Soon, another rover, Opportunity, will join it on the opposite side of Mars.

I look forward to watching future missions, manned and unmanned, perform risky and demanding feats. Then, as now, my attention will remain on the face that isn't smiling and wonder what he or she knows.

Copyright © 1998-2005 Organization for the Advancement of Space Industrialization and Settlement. All Rights Reserved.