Selected Articles from

the

May 2001 Odyssey

Editor: Terry Hancock

- Gossamer Sails, Robert Gounley

- Theory of Light Sails, Terry Hancock

- The Surf Report, Diane Rhodes

Gossamer Sails

Robert Gounley

The idea is such a beautiful thing: Drape silver sheets against the starry sky and let sunlight hoist you through space. Even the name, ``solar sailing,'' conveys dreamy images of clipper ships plying a new ocean. It sounds too fanciful for science fiction - more nearly it smacks of being the favored transport of wizards and fairies.

Solar sailing is no fiction! While it will never do the heavy lifting much space travel demands, there are niches this technology can fill well - and, perhaps, inspire a few poets. Best of all, one will soon be coming to a sky near you.

First, we must dispel an unfortunate mixing of metaphors - solar wind does not drive solar sails. What we call ``solar wind'' are streams of energetic subatomic particles pouring out of the Sun. Any material thin enough to be called a sail allows solar wind to pass through it like fishnet. (Magnetic sails that can harness this energy are a theoretical possibility, but are much further from first flight).

Sunlight is a different matter: Light imparts gentle pressure on any surface it contacts. On Earth, friction overwhelms the ability of solar pressure to move things about. In the hard vacuum of space, though, even this tiny force can accumulate and push things about.

The importance of solar pressure was learned early in the Space Age. The first communication satellites, appropriately named ``Echo,'' were giant silver balloons designed to reflect radio signals back down to the Earth. They were completely passive, yet day-by-day operators noticed their orbits were slowly changing. With nothing to compensate for the solar pressure, each balloon was sped up when it traveled away from the Sun and slowed down when it traveled toward it. In the end, the satellites were pushed into useless orbits. Ever since, solar pressure has mainly been known as a ``disturbance force'' that mission planners consider when planning a satellite's orbit.

Still, some space scientists realized that solar pressure could be a potential way to travel about the solar system without the encumbrances of rocket engines or their fuel. The key is patience. Even with a sail kilometers square, the acceleration will scarcely be felt. Gathering the speed desired might take years, but it comes with little more effort than tilting the sail at the correct angle to produce the desired result. Given enough time, you can go anywhere.

The trick is to build light: For greatest efficiency, solar sails must be made very thin and highly reflective - typically using metal-coated plastic sheets. In effect, solar sails are sailing ships made from holiday gift-wrapping.

The frailty of solar sails is a concern that has kept the idea from more rapid development. Even under the steadying effect of Earth's gravity, the engineer is seriously challenged with handling a one-meter square section of gift-wrapping. In space, the sails must be carefully unfurled, then stretched like a kite lest they flop about like a loose newspaper on a windy day. For the least mass, struts could be made from inflatable tubes. For still greater stiffness, the whole assembly might be spun like pizza dough. (Any thoughts who an advertising agency would visit to sell this space?)

Of course, solar sails work best near the Sun, inside of Earth's orbit. Tilting the sail and making clever use of orbital mechanics, a small payload can be successively pumped onto trajectories allowing them to coast towards the outer planets. Beyond that, powerful lasers might someday be called upon to give a little extra boost to a distant sail.

In the 1970s, solar sails gained NASA's attention. Several nations had plans to send spacecraft to study Comet Halley when it flew by in 1986. Given the comet's speed and direction, the best conventional rockets could do was hurl each spacecraft on a path crossing through the coma. Opportunities for close observation would be fleeting.

The ideal course would have a spacecraft pull alongside the comet and study it closely for months. A large solar sail with a small payload could do that, but none had ever been built. The risks seemed too high for a mission of such importance. The idea of solar sails was put aside and more conventional missions, with considerably less capability, were considered instead. (In the end, no U.S. mission was launched to Comet Halley, although an existing spacecraft in a high orbit was redirected to encounter Comet Giacobini-Zinner one year before any other spacecraft could reach Halley).

For the past 30 years, supporters of solar sails have agitated to bring the idea off the drawing board. Now that is about to happen.

|

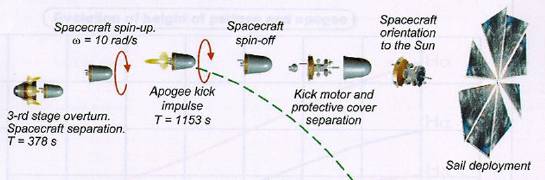

| Detail of Cosmos-1 2nd Phase Mission Profile. Illustration: Babakin Space Center, © The Planetary Society Click for full illustration (708K bytes) |

The Planetary Society is supporting the solar sail project called Cosmos-1, honoring society co-founder Dr. Carl Sagan. Its first suborbital test flight launches this June and will be followed by an orbital launch between October and December. According to the Planetary Society website, the payload is``a 30-meter diameter sail, configured in 8 triangular blades and deployed by inflatable tubes from a central spacecraft at the hub. The 40-kilogram spacecraft will be launched by Volna, a submarine-launched converted ICBM, into a 850-kilometer circular, near-polar orbit of Earth.

``Once in orbit, the solar sail spacecraft will be as bright as the full moon (although only a point in the sky) and will be visible from places on Earth with the naked eye. Images of the sail in flight will be sent to Earth from two different cameras on-board the spacecraft.''

Now that is a sky-show worth running out to see.

For more information about the Planetary Society's Cosmos-1 project, visit The Planetary Society web site.

And be sure to ``watch the skies.''

Webmaster's Note: The launch of Cosmos-1 failed when the Volna rocket did not send the final separation signal that would have separted the spacecraft from the launch vehicle. Read the latest updates from the Planetary Society.

File translated from TEX by

TTH, version 2.25.

On 22 Jul 2001, 20:52.

Copyright © 1998-2003 Organization for the Advancement of Space Industrialization and Settlement. All Rights Reserved.