Search this Site

A Ringside Seat

By Robert Gounley

Saturn is a world of beauty and wonder. Backyard astronomers seek the honey-yellow orb banded by stunning rings. In the 1980s, twin Voyager spacecraft showed Saturn to be system of startling complexity: icy moons with vast craters, a giant moon with an atmosphere denser than Earth’s, and an intricate ring system with overlaid with spokes and braids. Over the past year, a new mission has unveiled new wonders that are helping us understand how the outer solar system formed.

OASIS guide was Steve Edberg from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Looking like an explorer in his khaki hiking clothes, Steve dazzled an audience at the Long Beach Public Library with his lecture about the mission of the Cassini spacecraft and Huygens probe. Orbiting Saturn, Cassini is a robotic observatory to study the planet, satellites, and rings. Having penetrated the dense clouds of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, Huygens unveiled a strange land of methane rain and icy boulders.

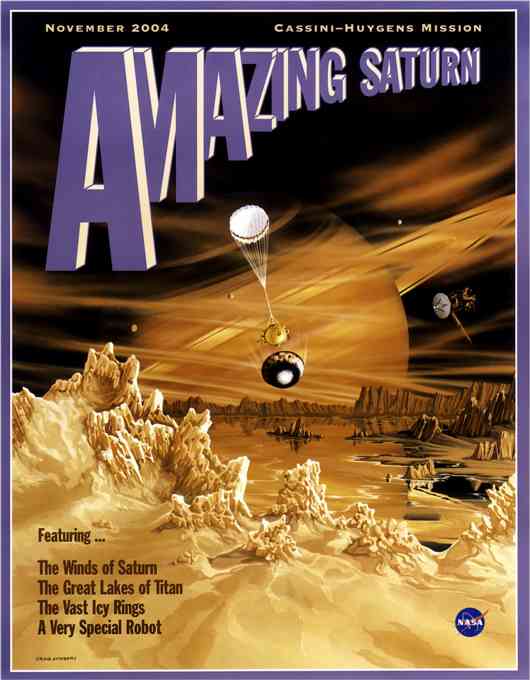

|

| Flyer for presentation on Cassini and the Rings of Saturn by Steve Edberg |

Built and operated by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the Cassini spacecraft is the size of a small bus with a large dish antenna on one end, and twin rocket engines on the other. In between, large tanks held the rocket fuel needed to guide Cassini on its voyage to Saturn and to slow it down for orbital capture. Riding on Cassini’s sides are a bevy of science instruments: cameras to see visible, infrared, and ultraviolet light; sensors to measure magnetic fields, radio waves, and plasma waves; detectors to monitor ionized particles and dust. With this Swiss Army Knife about Saturn, scientists have all the tools needed to probe moons, rings, radiation belts, and atmospheres.

Riding with Cassini to Saturn was Huygens—a dish-shaped atmospheric probe roughly the size of a toddler’s backyard swimming pool. Built and operated by the European Space Agency, Huygens was released for a fiery entry into the atmosphere of Titan in January of this year. When sufficiently slowed by its heat shield, Huygens deployed its parachutes for a gentle descent onto the moon’s surface. All the while, the probes science instruments measured the atmosphere and took panoramic pictures of the ground approaching below.

The past year has been busy for Cassini’s and Huygens’ Earthbound team of scientists and engineers. They’ve learned much and are eager to share their findings.

Saturn’s atmosphere is mostly hydrogen and helium with only traces of other gasses to show the faint imprints of clouds and atmospheric bands. Its serene appearance masks violent winds blowing 1100 miles per hour near the equator. Cassini’s cameras show, for the first time, shadows on lower altitude clouds that reveal the three-dimensional structures of high altitude clouds above. Bright flashes on the planet’s night side confirm the presence of lightning indicated by characteristic radio signals Cassini detects over the whole planet.

|

| Steve Edberg at Long Beach Public Library. |

In many Cassini pictures, Saturn's clouds appear in same soft yellow tones we can see from Earth. The audience blinked when shown a picture where the cloud tops appeared deep blue with black stripes. There, Cassini glimpsed a section of the planet lit only by sunlight streaming through the rings. To scientists, the patterns of filtered light and shadow give clues to the size and clustering of ring particles. To artists, it looks like a vast lace curtain shades the planet.

The rings are among the grandest and most enigmatic sites in the solar system. From Earth, we see the rings as a few broad, flat surfaces separated by broad gaps. Up close, they show themselves as thousands of distinct narrow rings. Some have sharp edges, while others show scalloped edges and patterns like spiral eddies. At these irregular boundaries, Cassini often finds small moons orbiting in the gaps. Like a boat’s wake through still water, the gravity of these moonlets disrupts the otherwise regular motion of the ring particles about the planet.

Some features, which earlier spacecraft found on Saturn’s rings, are now strangely absent. Twenty years ago, the two Voyager spacecraft saw radial patterns rotating along with the rings like the spokes of a wheel. Today, none are seen. For reasons not yet fully understood, the rings continually refashion themselves in subtle ways visible only to spacecraft nearby. Cassini will watch for new acrobatics.

Cassini’s orbits have been carefully choreographed to make many close flybys of Saturn’s satellites. Back when astronomers knew only nine moons, school children memorized their names using the abbreviation “MET DR. THIP” (Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, Dione, Rhea, Titan, Hyperion, Iapetus, and Phoebe). Since then, over forty more have been discovered, and Cassini continues to find more. Scientists who give names to these newly found moons must now plumb the back pages of mythology textbooks for increasingly obscure supernatural beings—Erriapo, Ymir, and Albiorix—for example. Any mnemonic to remember all these satellites will use most of the alphabet.

Through Cassini’s eyes, Saturn’s moons are more than mere points of light; they’re distinct worlds with characteristic features and movements. Small moons like Hyperion are irregular lumps so misshapen they don’t rotate so much as tumble and wobble through space. Mimas is round, but bears a crater so large many call it the “Death Star”. Iapetus is a veritable yin-yang satellite with one side bright as snow and the other dark as black velvet. If that weren’t strange enough, a ridge 10—20 km high and nicknamed the “belly band” wraps around Iapetus like a carelessly exposed seam.

As befits its name, Titan dominates all other objects orbiting Saturn. Larger than our own moon, it is our solar system’s only satellite with a dense atmosphere. This mixture of organic compounds forms a golden haze that envelops the body. With radar and infrared detectors Cassini can detect large features, but it was Huygens that gave us our best possible view early this year. While the probe turned and twisted below its parachute, its cameras caught a panorama looking like an aerialview above one of Earth’s coastlines. Features resemble ocean coves and ancient riverbeds. Whatever formed them must flow at temperatures so cold that water is a mineral to be shaped and eroded by winds and whatever passes for rain. Liquid methane and ethane, the stuff of natural gas, are the best candidates.

Against long odds, the Huygens continued operating all the way to the surface and for many minutes afterwards. At touchdown, sensors felt the surface gently crunch beneath the weight of the probe. Gourmands in the scientific community declared it had the consistency of crème brûlée. Even without a taste test, the Huygens mission earned a four-star rating. Scientists will feast on its data for years.

The exploration continues. Steve Edberg used over 100 slides in his hour-long talk just to give a representative sample of all that Cassini and Huygens have found just in their first year at Saturn. Cassini’s mission is designed for at least three more years and the spacecraft should operate in an extended mission for years longer.

Thanks to speakers like Steve, we can all get a personal tour.

Copyright © 1998-2007 Organization for the Advancement of Space Industrialization and Settlement. All Rights Reserved.