|

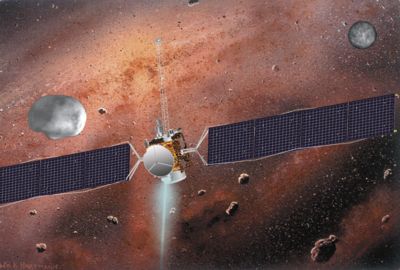

| Dawn with Vesta and Ceres against Hartmann background. Credit: Background painting, "A cocoon nebula, perhaps the primoridal solar nebula" by William K. Hartmann. Courtesy of UCLA |

Dawn Rising

By Robert Gounley

I just bought a house.

It’s pretty old and the repairs multiply daily. To relieve the drudgery, I’ve learned to play “home detective”. In odd corners, paint flecks and wood chips lay untouched for years. Study them and you can recreate where a wall had once been, how stereo speakers had once been wired, and when (shudder) window frames had once been painted turquoise. In the walls and under the floors, the master craftsmen who built my home left delicate shavings to commingle with the coarse grit from successive generations of do-it-yourself repairmen.

All this comes from studying scraps. In a way, it reminds me of my day job.

The project I work on will explore a largely unstudied portion of our solar system – the main asteroid belt. Few asteroids are larger than a hundred kilometers in diameter. Most of the 5000+ detected by earthbound telescopes are the size of mountains. Millions more, the size of boulders, are as yet undetected. Taken together, they could hardly form a moon around Jupiter or Saturn.

Yet they have a lot to tell us about our solar system. They’re the building scraps left over from when the Sun and planets. Study them and we’ll glimpse things as they were billions of years ago when dust and debris began gathering into larger bodies. Appropriately, the mission is called “Dawn”.

It takes a special spacecraft to do this exploring. Just getting to the main asteroid belt takes a lot of energy. Along the way, Dawn will fly past a few small asteroids before changing speed to orbit one of the largest asteroids – Vesta. There, it will change speeds several times to vary the orbit for different science observations. Cameras and sensors will map the surface and gather clues to its mineral composition. After a year’s exploration, Dawn will change speed once more to leave Vesta and fly by another small asteroid, or possibly orbit the largest asteroid – Ceres.

Changing a spacecraft’s speed isn’t difficult, but it is rocket science. Traditionally, that means rocket engines burning lots of chemical propellant. Conventionally, Dawn’s mission would require very big propellant tanks. A big spacecraft takes a big launch vehicle to put it into space. Costs become enormous. That sticker shock kept most asteroid mission proposals entombed in file drawers.

(One very successful mission – called Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous or “NEAR” – completed a yearlong study of the asteroid Eros. However, the path Eros takes around the Sun made getting there much easier than Dawn’s mission.)

For Dawn to do its mission, at a price taxpayers are willing to pay, takes some unconventional methods – ion propulsion. Rather than carrying explosive and toxic rocket fuel, Dawn’s ion engines will use an inert gas xenon for propellant. Xenon atoms are given an electric charge, allowing magnetic coils and electric grids to eject them into space. This ion stream propels Dawn.

The pale blue glow of an ion engine looks remarkably like the warp engines in Star Trek, but don’t expect to be thrown back in your seat. The force one engine applies to Dawn is no stronger than the force you can apply blowing onto the palm of your hand. Ion propulsion’s huge benefit is that its thrust requires only electrical power (readily available from solar arrays) and the gentlest trickle of xenon. Where chemical rockets exhaust their propellant supplies in minutes, ion engines can operate continuously for years. In the end, endurance wins out over momentary displays of power.

Ion propulsion is no laboratory curiosity. It got a test drive five years ago in the technology demonstration mission Deep Space 1. That success lead to the creation of the Dawn mission.

It’s been my good fortune to be on the team developing Dawn. From time to time I hope to share with you some of the joys and disappointments that come with space exploration.

The Dawn mission launches May 2006, reaching the asteroid Vesta in 2011. Perhaps by then, I’d be done fixing my house.

For more information about the Dawn mission, see www-ssc.igpp.ucla.edu/dawn/.

Copyright © 1998-2005 Organization for the Advancement of Space Industrialization and Settlement. All Rights Reserved.